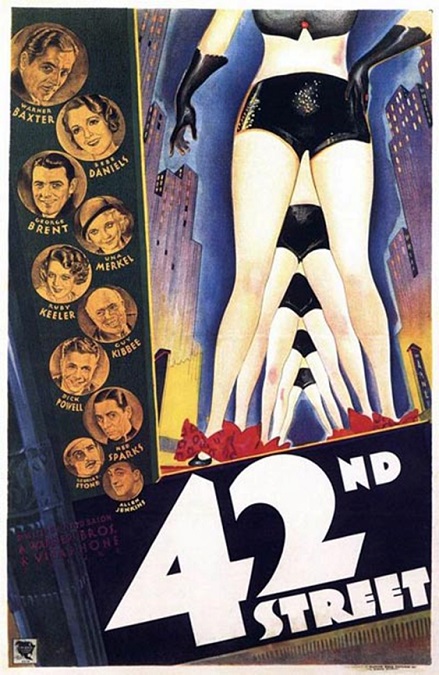

42nd Street – 1932 / 1933

This film is an icon of the American Film Musical. It starred Warner Baxter as Julian Marsh, the harsh Broadway director who puts his heart and soul into putting on the best show of his career during the great depression, a risky move. With him was Bebe Daniels as Dorothy Brock, the aging star hired to take the lead in his show. George Brent played Dorothy’s love interest, Pat Denning. The inexperienced chorus girl who could dance rings around any other dancer was Peggy Sawyer, played by Ruby Keeler. And finally, Billy Lawler, played by Dick Powel, took on the role of the show’s leading man who falls in love with her.

From there, the plot is a little shallow, but that’s OK, because it is really secondary to the dancing. After all, first and foremost this is a dance show. Any time you put over 40 women who know how to dance and show off their legs on the stage at the same time, everything else is secondary. And that fabulous kick-line is the money-shot, what we all came to see.

And boy, does this film deliver. There were more legs in this movie than I could count. Ruby Keeler did a great job tapping her tootsies and singing her heart out. The big number in the show is the name of the film, 42nd Street. It is really an exciting number, both visually and aurally.

It is important to note that in 1980 this incredibly popular 1933 movie musical was turned into an actual stage show that won the Tony Award for Best Musical and became a long-running Broadway hit. It was revived again in 2001, winning another Tony Award for Best Revival, a performance, I was lucky enough to see. Obviously, the show has credibility and staying power.

One of the problems I have with most movie musicals of that era is that the songs are completely unmemorable. But that is part of the magic of 42nd Street. It has several songs that stick in your head and heart. There is the title song, of course, along with You’re Getting to Be a Habit With Me and Shuffle Off to Buffalo. In my opinion, a memorable song or two is absolutely necessary to make a successful musical.

The plot, while deceptively simply (or maybe not so deceptive…) is fun and light-hearted. There are a few lines of the stereotypical catty nature of women in competition with each other, my favorite one being, “It must have been hard on your mother, not having any children.” But for the most part, the women were all ladies of integrity and honesty.

In that respect, it is always pleasantly surprising when the character of Dorothy Brock fractures her ankle the night before the opening performance, and the rich financer of the show wants to replace her with his new girlfriend Ann Lowell, played by a very young Ginger Rogers. She actually shows an uncharacteristic strength of character. She acknowledges that Peggy is a better dancer than any of them and actively gives up her chance of becoming a big star so that Peggy can play the part. She does this all for the sake of the show.

And you might think that Dorothy would hate Peggy for “stealing” her part, despite the broken ankle, but she visits Peggy before the show starts. With grace and kindness, she encourages the inexperienced actress and gives her advice on how to become a super-star. She says that she’d had her chance and now it was the younger girl’s turn. It left me with a nice feeling.

Dick Powel was particularly fun to watch. He was handsome and could keep up with Keeler’s dance steps easily. Keeler, herself did a fantastic job, and was a pleasure to watch.

One last thing that made little sense to me was a choice made by director Lloyd Bacon and choreographer Busby Berkeley. When they had the women on the stage of their show, they had them in the formation of a circle making moving patterns with their legs that nobody in the fictional audience would ever be able to see. Only a movie camera placed above the dancers looking down into the center of the circle would be able to see the intricacies of the choreography. It was a fantastic visual for the film, but made no sense in the fictional plot.