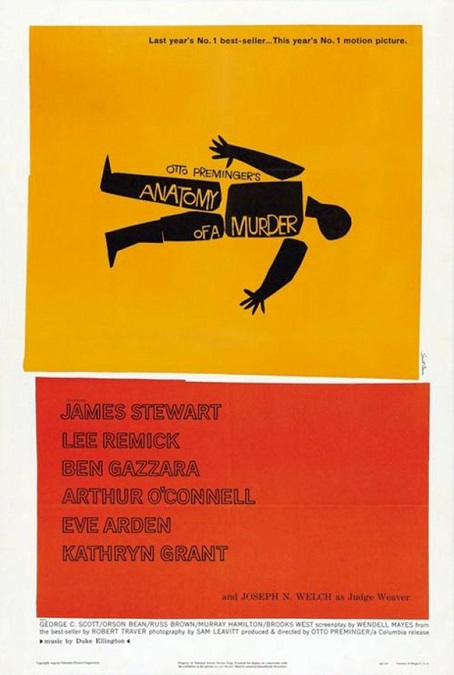

Anatomy of a Murder – 1959

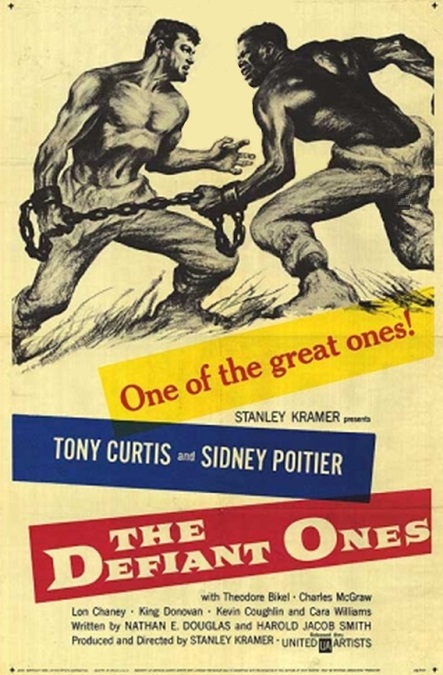

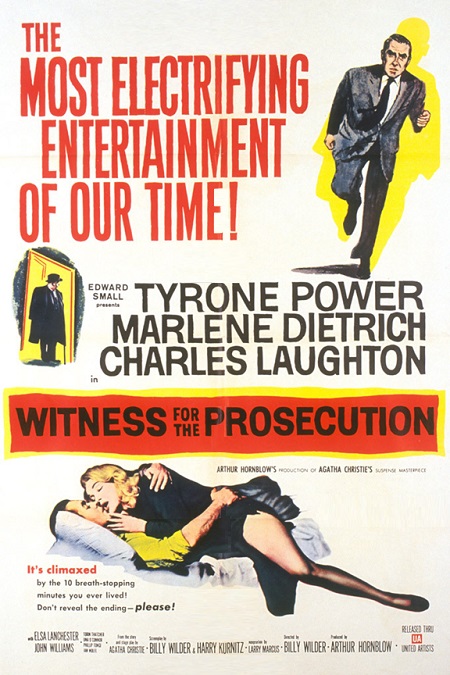

Here we have another courtroom drama, the last one being Witness for the Prosecution in 1957. 1957 has the distinction of being the year the hit TV show Perry Mason began its first season. Hmmm… This movie stars James Stewart, Lee Remick, Ben Gazzara, Arthur O’Connell, Eve Arden, Kathryn Grant, and George C. Scott. Quite an impressive list of names.

Stewart, of course, played the lead, a country lawyer named Paul Biegler. He was a simple man who loved fishing more than anything else. His friend and fellow lawyer whose career has tanked because of his alcoholism, is Parnell McCarthy, played by O’Connell. Arden was wonderful as Biegler’s secretary. The case that was the centerpiece of the film is that of Fredrick Manion, played by Gazzara, an Army officer who has murdered a man for allegedly raping his wife, Laura, played by Remick.

The question is not whether Manion has committed the murder, but whether Manion was in control of himself when he did it. The plea? Irresistible impulse, otherwise known as temporary insanity. The prosecuting lawyer, played by Brooks West is an idiot, but he brings in a big-shot lawyer, Claude Dancer, played by Scott, to help him win the case, which ended up involving not only murder, but spousal battery, and rape.

In general, the movie was competently made, but I have to mention a few things that I felt to be poorly done. For example, the filmmakers kept trying to throw unnecessary humor into the script. That, in itself, isn’t a bad thing, but it was poorly executed, and here’s why. Whenever a witness, or a lawyer, or even the judge said something amusing, you would hear a pre-recorded laugh track that would have done well on a low-budget TV sitcom. But if that weren’t bad enough, it wasn’t even done right. The people laughing were supposed to be the audience at the trial, which could be clearly seen behind the lawyers. However, I noticed that when you could hear them laughing, not a single spectator was moving a muscle. They all appeared stone-faced and serious. Huh?

Another thing that caught my attention was the music. In my research, I found that the music was supposedly something special and spectacular, but I just don’t agree. Duke Ellington wrote a jazz score which has been described as evocative and eloquent. But to me, it just sounded jarring and inappropriate, meaning that it didn’t always seem to fit. A film score is supposed to compliment the action taking place on the screen, but more often than not, Ellington’s crazy score dominated the film and distracted me from what was happening like an obnoxious bully.

But I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the remarkable acting. The talented cast all did a great job, but I need to point out Remick, Gazzara, Arden, and Scott as stand-outs. Scott, in particular, did a good job. He was almost portrayed as the bad guy, or at least the guy who is opposing our hero, Stewart. He seemed to be ruthless in his pursuit of a guilty verdict. When he got into a witness’s face, the camera angle they used made it seem like he was getting into my face, making his cross-examination even more intense.

And finally, I have to make mention of something that I found interesting, only because I know this movie came out in the late 1950s. It was a time when certain things were just not discussed in public, a time when the Hays code was still in effect, a time when the use of a certain word would have surely been controversial. The prominent use of the word ‘panties,’ I imagine, must have been quite a surprise to many people. But the film made the decision to be refreshingly adult and matt-of-fact about the scandalous word.

I thought it was smart of the filmmakers to have the judge say, “For the benefit of the jury, but more especially for the spectators, the garment mentioned in the testimony was, to be exact, Mrs. Manion’s panties. (The spectators laugh loudly) I wanted to get your snickering over and done with. This pair of panties will be mentioned again over the course of this trial, & when it is, there will not be one laughter, one snicker, one giggle or even one smirk in my courtroom. There is nothing comic about a pair of panties that resulted in the violent death of one man, & the possible incarceration of another.” Yes, you 1959 audiences. It’s just a word. Get over it.