Zorba the Greek – 1964

Zorba was an interesting character. He seemed to epitomize the general feel of the entire film, which was that sometimes life is up and sometimes it is down. Either way, it should be lived to the fullest. It is a great philosophy, but part of its challenge is being happy, even in the face of tragedy.

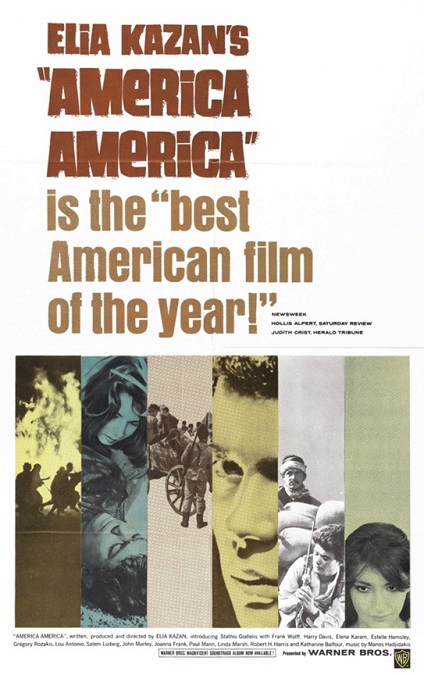

As I watched the film, the first thing that struck me was that it reminded me very much of the 1963 Best Picture nominee, America, America. It seemed to have a number of clear similarities in the cinematography, directing, and even the script. They both offered the viewer a look into the culture of the Greek people, both touching on the animosity between the Greeks and the Turks.

Anthony Quinn played the title role of Alexis Zorba. He is a jack of all trades with a long and hard history. But he has one peculiarity that is a significant part of the plot. There have been a few times in his life, during periods of great depression or great joy, when he dances. He dances until he drops from exhaustion as a way to purge emotions that are too intense to bear.

But Zorba is not the protagonist. The film is really about a young Englishman he meets who happens to own a mine in Crete. His name is Basil, and he is played by Alan Bates. He meets Zorba as he is going to his mine to make an attempt at turning it into a working enterprise. Zorba, who has had mining experience, offers to become his foreman.

Basil is a man who has a lot of trouble showing his emotions, setting him up as a good contrast to Zorba, who wears his emotions on his sleeve. Their relationship is an odd one. They start out as strangers, and become employer and employee, and finally friends. Along the way, they each experience love in their own ways, and in the end, Basil asks Zorba to teach him to dance, or to metaphorically embrace life.

The story is really Basil’s and follows the deep and profound life-lessons he learns from Zorba. And as far as I can tell, the lessons seem to have a specific kind of philosophy. Take life as it comes and appreciate your fortunes, both good and bad. Go where the wind blows you and know that wherever you land is exactly where you are meant to be. And don’t put too much stock in what you read in books. Books can tell you about the world, but you will never know the world until you experience it for yourself.

Now, I have to mention an aspect of the plot that I found uncomfortable. Living in the village is a beautiful widow, played by Irene Papas. A young boy is in love with her, but she constantly rejects his advances. One evening, the local boy tries to get her attention and fails. That same night, Basil is finally seen going to her bed. But here is where it got weird. The young boy is told of the widow’s acceptance of a lover and so he drowns himself. The next day, the boy’s father, along with the entire town, stones her in the streets. Basil is too afraid to save her so he sends for Zorba. Zorba comes to rescue her, but the dead boy’s father slits the widow’s throat. Everybody seems to be OK with the murder. Never-mind the fact that the widow never pretended to accept the boy’s affections, and she was not responsible for his suicide. I didn’t understand why everyone wanted her dead.

Another strange part of the story had to do with the character of Madam Hortense, played by Lila Kedrova. She is an older foreign woman who owns the local hotel. She has money and falls for Zorba. He is eventually tricked into marrying her, but soon after the wedding she falls ill and dies. The instant she is dead, the evil villagers fall upon her house like vultures and steal her every possession, leaving Zorba with nothing more than a parrot.

But all is well. Basil learns to dance away his pain, both at losing his lover and possibly being the cause of her death. Zorba teaches him to dance away the loss of all his money and business ventures. He dances until he is happy and is able to leave Greece. It was a strange ending, but appropriate enough, I guess. After all, when you have lost everything, what else can you do but embrace life and try to be happy?