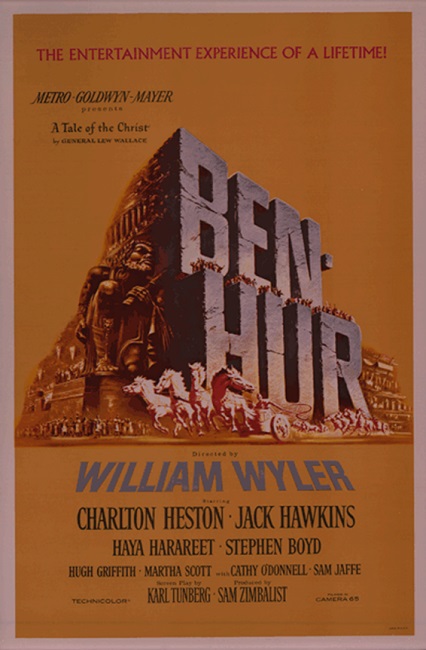

Ben-Hur – 1959

The 1959 Best Picture winner is a big one. Here we have a great film which had incredible production values, an awesome score worthy of the emotionally powerful story being told, thousands of extras, each of whom needed to be dressed in period specific clothing, an epic story on a mighty and grand scale, a capable cast of actors, and an attention to detail in the sets and costumes that was staggering. I would even venture to say that in scale and scope, Ben-Hur is able to hold its own with films like 1939’s Gone with the Wind and 1997’s Titanic.

A few Interesting notes: Director, William Wyler, spearheaded the film that won 11 Academy Awards, a record that was not matched until Titanic in 1997 and again by The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King in 2003. Ben-Hur had the largest budget and the largest sets built for any film produced. The nine-minute chariot race has become one of cinema’s most famous sequences. The score composed by Miklos Rozsa was highly influential on cinema for more than 15 years, and is the longest ever composed for a film.

This incredible version of Ben-Hur was not the first version of the story ever filmed. The original book, Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, written in 1880 actually spawned two film versions in the silent era, one in 1907 and another in 1925. There seems to be no question that this is one of the most successful films in the list of Best Picture winners. The question I need to answer is: why? I’m not disputing that the movie deserved all the awards it won. I think it deserved them all. But what was it that made this movie so great? Many things. It had a great director, great cast, great score, great costumes, great sets, and great story.

Wyler really seemed to know what he was doing. He was incredibly ambitious. His vision of the grand and epic scale the film needed was spot-on. The huge number of extras provided an anchor of reality to the story that was set in ancient Rome, and yet at times, he knew when to delve into the realm of the supernatural, portraying biblical miracles with finesse and subtlety. In particular, the very first scene of the film was the Nativity of Christ. It was done so beautifully that I was nearly brought to tears by the imagery on the screen.

The character of Judah Ben-Hur was certainly a believable hero. He was flawed enough to be completely human. He was real enough to fall victim to his own dangerous passions. He allowed himself to be driven by hate and a need for revenge, a path that can only lead to self-destruction in the end. But even after that revenge is won, it seems to be a hollow victory. We see him fall into the dark depths of despair, and we see him lifted back into the light as he is changed, redeemed by his encounters with the man Jesus.

Judah Ben-Hur is played by Charlton Heston, a man who many consider one of the greatest actors of all time. I feel he performed adequately in Ben-Hur, turning in a deep and emotional performance. The role itself required an actor that has a strong yet vulnerable personality, someone who was able to portray the heights and depths of love, anger, and despair. Heston did it all well enough, but I have always found his acting style to be a little forced, his movement stilted, and his delivery a bit jerky, as if he is trying too hard to be “dramatic.”

Playing opposite Heston was Haya Harareet, performing the role of Esther. As Judah’s love interest, Harareet did a great job, exuding a calm and subservient demeanor. She was absolutely gorgeous, and was able to convincingly cry on cue – not an easy thing to do. Another stand-out member of the cast for me was Stephen Boyd as Messala, Judah’s boyhood friend. The main plot opens as Messala returns to Jerusalem as a Roman tribune and commander of the local Roman garrison, charged with rooting out and arresting Jews who criticize the Romans. The trouble is that despite the fact that they were once friends, Judah Ben-Hur is a Jew who is not at all happy with how his people are treated at the hands of the Roman conquerors.

When Judah refuses to turn in any of his people, Messala finds an excuse to persecute him in the worst way. He is unjustly accused of a crime, and not only is he arrested, but his mother and sister are arrested as well. Of course, he swears revenge before being shipped off to become a galley slave. But his chance meeting with Jesus of Nazareth changes his life in ways that he cannot possibly comprehend. Whose life would not be changed by such an encounter?

Boyd did a great job. At first you like him. While he and Judah are still getting along, they actually share a strange relationship, which I found to be a bit homoerotic. They expressed a peculiar love for each other that seemed to go a bit beyond fraternal affection. I thought it odd, and nearly dismissed it as my imagination, but in my research, I found that I was not the only viewer to sense the homosexual tension in that scene. Then after Judah is arrested, Messala shows his true colors and he instantly becomes the bad guy. You want to see him get his just desserts.

And does he ever! Skip ahead to the great chariot race which was amazing to watch. The way it was filmed, the dramatic tension, the fast paced action, the incredible stunts, the way it captivated my attention – it was phenomenal! The supremely arrogant Massala, despite using tactics that could only be called cheating, not only loses the race, but loses his life in the process! There is a reason the chariot race sequence is one of the most famous scenes in cinema history. Audiences loved it and so did I.

Interesting note: The chariot race was filmed in a rock quarry outside of Rome. The economic situation in Italy was fairly poor at the time and 7000 people answered the casting call to be employed as spectators at the race. However, on June 6, 3000 people showed up, though only 1500 extras were needed. The crowd rioted, throwing stones and assaulting the set’s gates until police arrived and dispersed them.

Another interesting note: The chariot arena was modeled on a historic circus in Jerusalem. Covering 18 acres, it was the largest film set ever built at that time. Constructed at a cost of $1 million, it took a thousand workmen more than a year to carve the oval out of the rock quarry.

And finally, I have to mention the music. It was wonderful! Miklos Rozsa, of course, won his Oscar for the score. It was grand and majestic, and it blended seamlessly with the action taking place in the film. Many critics consider the score for Ben-Hur to be Rozsa’s greatest work, though at the time he was writing the music for most of MGM’s epics. It is interesting to note that he also composed the score for another Best Picture sinner: 1945’s The Lost Weekend.

This was an impressive movie on so many levels. The plot was full of action, but the underlying emotional content of the film was never absent. I have never been a huge Charlton Heston fan, but I have to admit he did a great job, and so did his talented supporting cast. But the film was really a wonderful conglomeration of effort from the thousands of people involved in its making. So I think the biggest applause has to go to director, William Wyler. The film’s greatness is due in large part to his brave and ambitious vision. Well done, Wyler. Well done.