A Clockwork Orange – 1971

I’m still trying to figure this one out. To start with, I think I’ll quote from Wikipedia’s article on the film to give a perfunctory telling of the basic plot and supposed meaning of the film. “A Clockwork Orange is a 1971 dystopian crime film adapted, produced, and directed by Stanley Kubrick, based on Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novella. It employs disturbing, violent images to comment on psychiatry, juvenile delinquency, youth gangs, and other social, political, and economic subjects in a near-future Britain.

“Alex, played by Malcolm McDowell, is a sociopathic delinquent whose interests include classical music, rape, and what is termed ‘ultra-violence.’ He leads a small gang of thugs, Pete, Georgie and Dim, played by Michael Tarn, James Marcus, and Warren Clarke, respectively. The film chronicles the horrific crime spree of his gang, his capture, and his attempted rehabilitation via controversial psychological conditioning.”

The plot was easy to follow, but there seemed to be a lot of symbolism in the movie that represented things of which I have no knowledge or understanding. I believe the film was supposed to be commenting on different forms of government like communism, totalitarianism, and fascism. I don’t know enough about any of these things to comment on them competently. It also comments on things like juvenile delinquency, behavioural psychology, and aversion therapy, subjects of which I have only a rudimentary understanding.

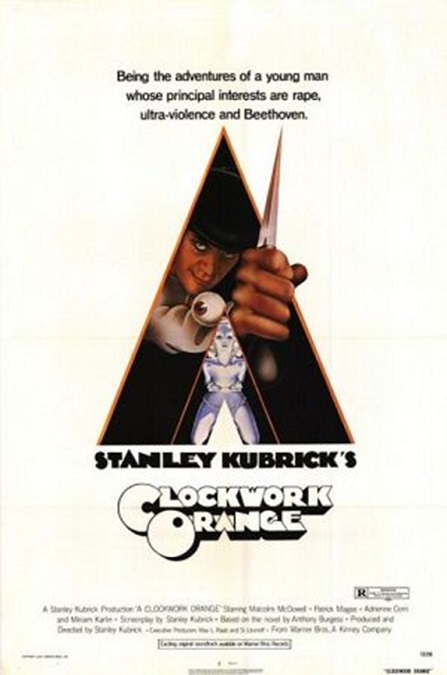

I think that there were many things in the film that I just didn’t understand, and what I got out of it was mostly on the surface: the basic plot, the interesting characters, and the unique imagery. So those are the things I’ll be focusing on. We have come to associate that iconic image of Alex DeLarge, all dressed in white with the black bowler hat, with violence and fear, and with good reason. The extreme cruelty and amorality that the character personifies is all the more frightening because Kubrick underscored it with music that was decidedly happy. Alex sang Singing in the Rain while savagely beating a man and raping his wife.

But these disturbing scenes of violence and rape are only in the first quarter or so of the movie, along with images of hard-core pornography, frequent shots of full-frontal nudity of both men and women, and pornographic graffiti and art. The rest of the movie follows Alex’s incarceration and his time in prison, and the equally cruel doctors who attempt to “cure” his psychopathic nature by brainwashing him. It is also clear that another major theme was the different political factions that wanted to use him and his horrible treatment to further their own agendas.

But later in the film, it became evident that the intense brainwashing not only didn’t destroy his violent nature, it ended up destroying his ability to live as a complete human being. As a result, when the victims of his violent past found him and enacted their revenge, he was not able to even defend himself. The horror in Alex’s eyes when he is faced with his former gang-mates, who were responsible for his arrest after a murder, is all too real. Now uniformed policemen, they beat him and nearly drown him.

By the end, I couldn’t tell what horrified me more: Alex’s psychotic and evil nature, or the cruel and inhumane methods that were employed to “cure” him, though I tend to think the former. Either way, I, like the character of the prison chaplain, played by Godfrey Quigley, who detested the aversion therapy that was used on Alex. They gave him drugs to make him sick, clamped his eyes open and forced him to watch images of violence and rape, conditioning him to get sick at the thought of such things. But the treatment was a failure because though it pacified his actions, it did not change his nature.

Alex was still evil. He still loved the raping and the violence, even though he could not act on it. And besides, the conditioning had the terrible side effect of making him just as sick whenever he heard his beloved Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, which is something worth loving. But the disturbing end of the film proved how pointless it all was, anyway. After his suicide attempt, his conditioning was broken, implying that he was once again free and eager to return to his psychotic criminal ways.

And finally, I need to mention a couple of the differences between the original book and the film, of which, I have learned, there were very few. But I think it is significant to know that in the book, Alex was much worse than the film depicted. In the book, Alex also drugged and raped two 10 year-old girls, and murdered a man while serving his prison sentence for sexually harassing him. But maybe those things were a little bit too much for Kubrick or the audiences of 1971, though with everything else that is shown in the movie, I can’t imagine why.