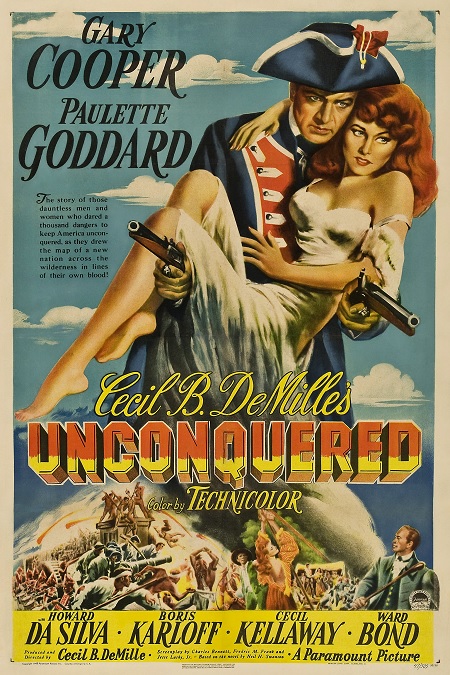

Tulsa – 1949 The Special Effects for this nominee come down to one thing: the big climactic scene in which there is a massive oil drilling fire. That was basically it for the entire film. The movie was like the previous 1940 Best Special Effects nominee, Boom Town. The only difference, really, was that the earlier film was in black and white, and this movie was in glorious Technicolor.

The Special Effects for this nominee come down to one thing: the big climactic scene in which there is a massive oil drilling fire. That was basically it for the entire film. The movie was like the previous 1940 Best Special Effects nominee, Boom Town. The only difference, really, was that the earlier film was in black and white, and this movie was in glorious Technicolor.

Now, that’s not to say that it wasn’t an impressive fire. In fact, it was on a scale that was staggering in its size and intensity. It was absolutely huge! There were oil towers exploding everywhere, flames consuming them as they toppled. There were roaring blazes billowing thick black smoke everywhere. It all started with a single match, but ended with dynamite explosions to cut off the conflagration.

Now, as far as the effects went, I expect that most of the burning towers were scale models, though I suspect that there were also some life-sized towers thrown into the mix. There were some pretty impressive shots of exploding oil drums, and one that even spilled its burning contents across the ground like liquid flame. Then, of course, the actors were composited into the blazing wreckage and choking smoke. There was even a herd of cattle being guided through the catastrophe.

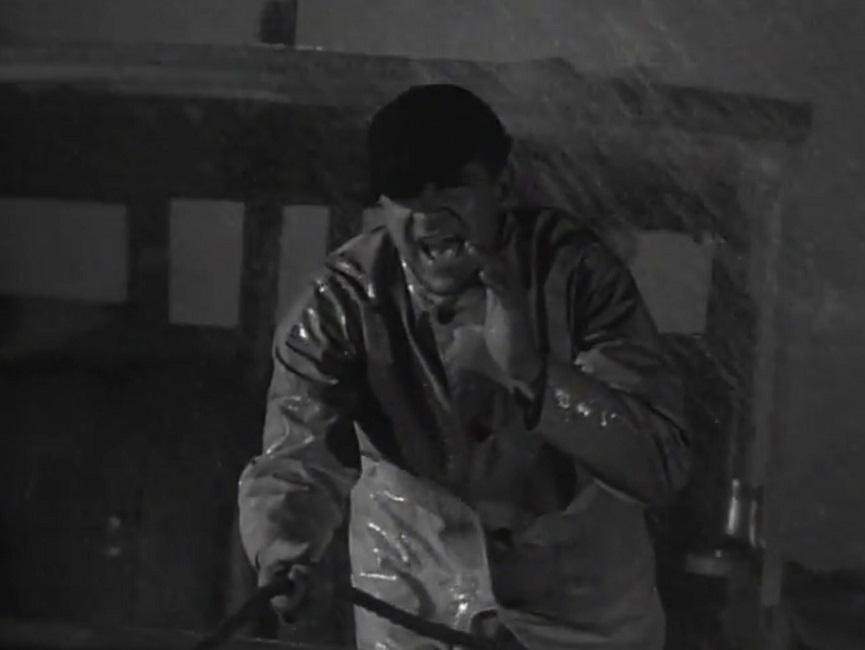

But the best shot of all was when the heroine, played by Rita Hayworth, gets trapped behind a fallen tower. The burning structure is so large, it hides her from view. So the hero, played by Robert Preston, jumps onto a bulldozer , covers himself with a blanket, tells the firemen to keep their water hoses fixed on him, and drives the construction vehicle into the flames. The camera follows him into the fire. We see the burning tower being pushed out of the way. We see the tongues of fire surround him on every side. Eventually the flames get between the bulldozer and the camera, and Preston disappears from view. Quite impressive!

And I mustn’t forget to mention that the sound mixing during this scene, which was still being considered part of the special effects by the Academy, really went a long way to create drama and intensity. The constant roar of the oil fire was nearly deafening, forcing the actors to shout their lines to be heard.

I can understand why the film was nominated for the Oscar, but I can also understand why it didn’t win. I think there were two main reasons. First, it was an effect that had been done many times before. In general, fire and explosions were nothing new to the big screen. And second, it was really the only scene in the whole movie that used any kind of notable special effects. Sure, there were a few oil or water geysers, but really, how hard could those have been? Just get some dyed water and a powerful water pump, and you have your effect. I expect more from a Best Special Effects Nominee.

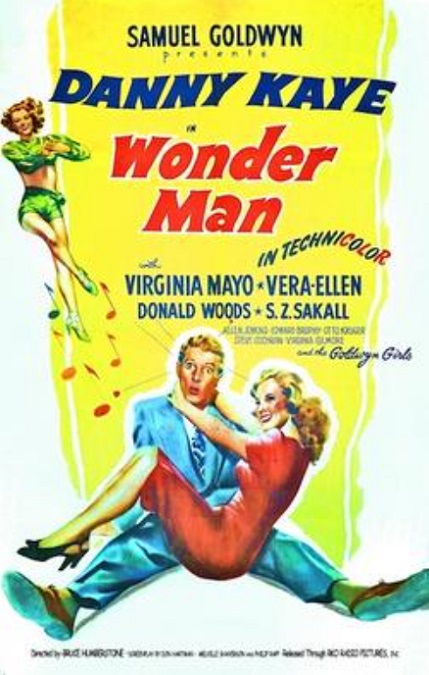

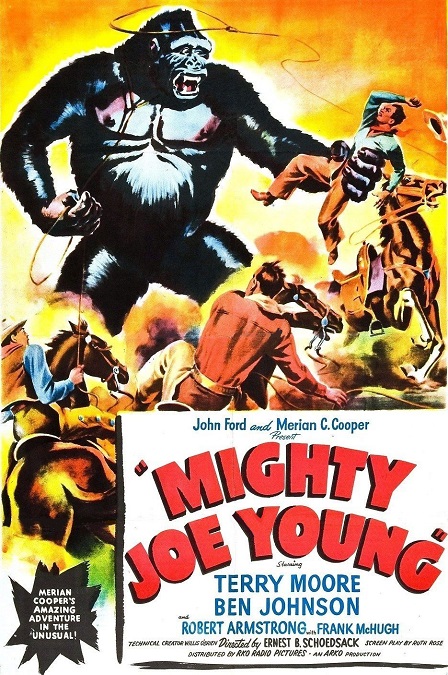

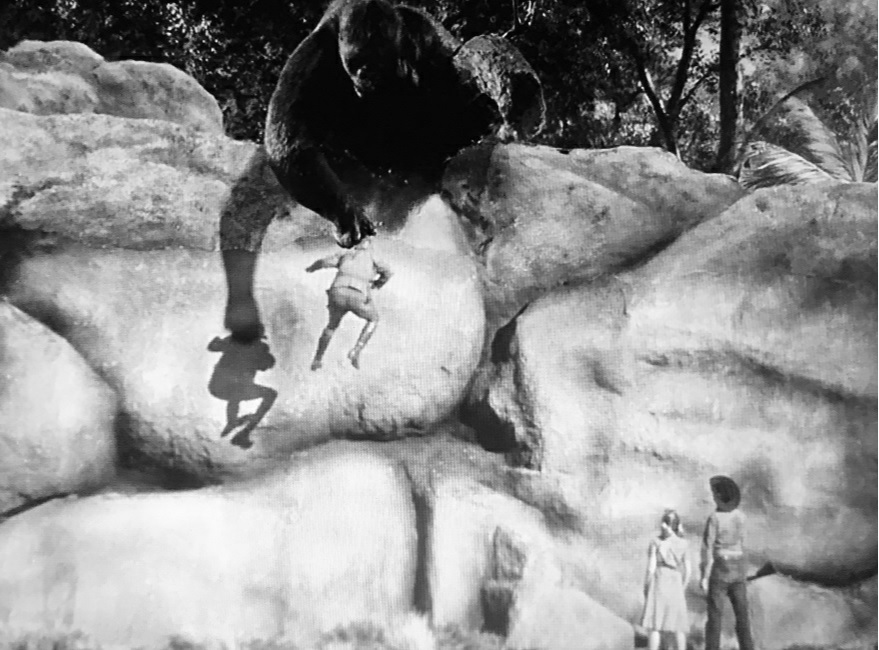

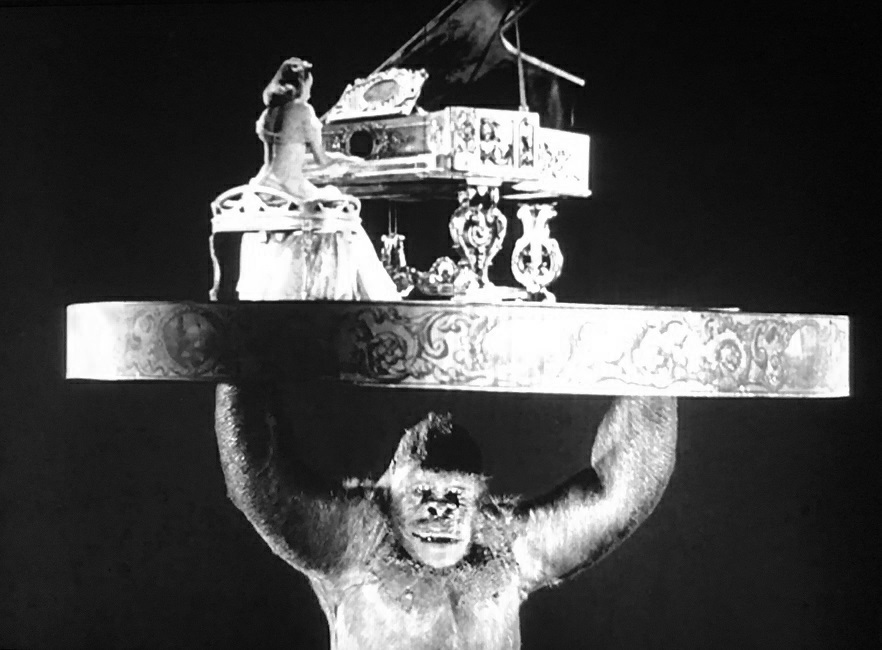

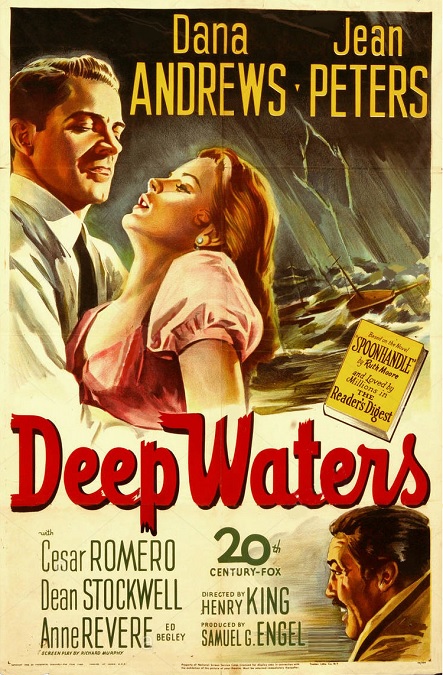

This was a great example of a special effects winner! There was a ton of effects, all of which were impressively executed. The film’s most creative and innovative effects were those of the stop-motion animation variety, though there was also a smattering of actual hand-drawn animation as well. And these were all composited together with live actors in a clever and surprisingly seamless way!

This was a great example of a special effects winner! There was a ton of effects, all of which were impressively executed. The film’s most creative and innovative effects were those of the stop-motion animation variety, though there was also a smattering of actual hand-drawn animation as well. And these were all composited together with live actors in a clever and surprisingly seamless way!

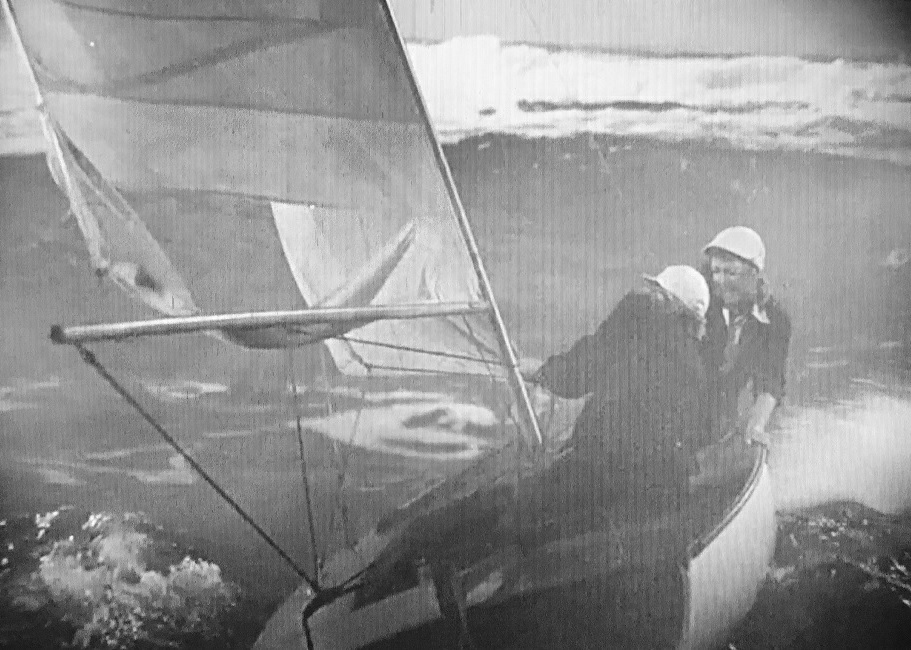

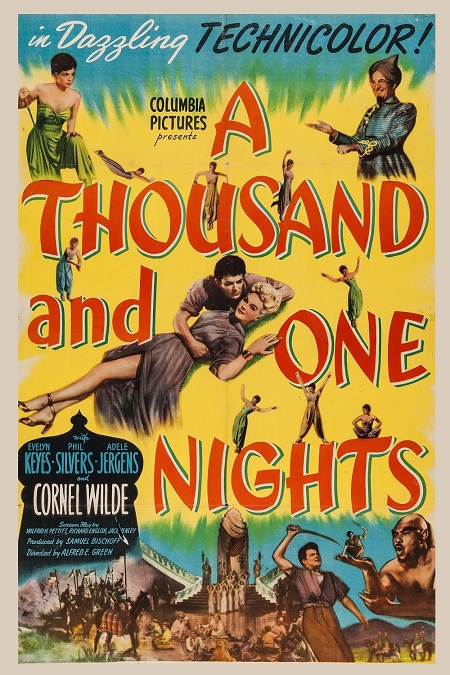

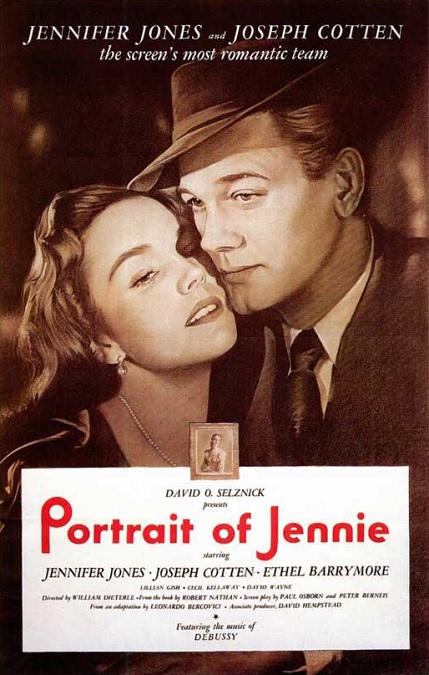

OK, am I being punked? What is going on here? This movie was one of only two that were nominated for Best Special Effects in 1948. Am I to believe that there was only one other movie that year with visual or sound effects as good as this one? The visual effects came down to a single scene! A single five minute scene! Other than a small handful of standard rear-projection shots, there was nothing!

OK, am I being punked? What is going on here? This movie was one of only two that were nominated for Best Special Effects in 1948. Am I to believe that there was only one other movie that year with visual or sound effects as good as this one? The visual effects came down to a single scene! A single five minute scene! Other than a small handful of standard rear-projection shots, there was nothing!

I found this to be, I’m sorry to say, a pretty dull movie. It was slow and predictable, and when it came to the special effects, I honestly wasn’t very impressed. By this time, Hollywood had been giving us better special effects for some time, and while a few of the effects were interesting, some even well-done, most of them were just average in quality.

I found this to be, I’m sorry to say, a pretty dull movie. It was slow and predictable, and when it came to the special effects, I honestly wasn’t very impressed. By this time, Hollywood had been giving us better special effects for some time, and while a few of the effects were interesting, some even well-done, most of them were just average in quality.