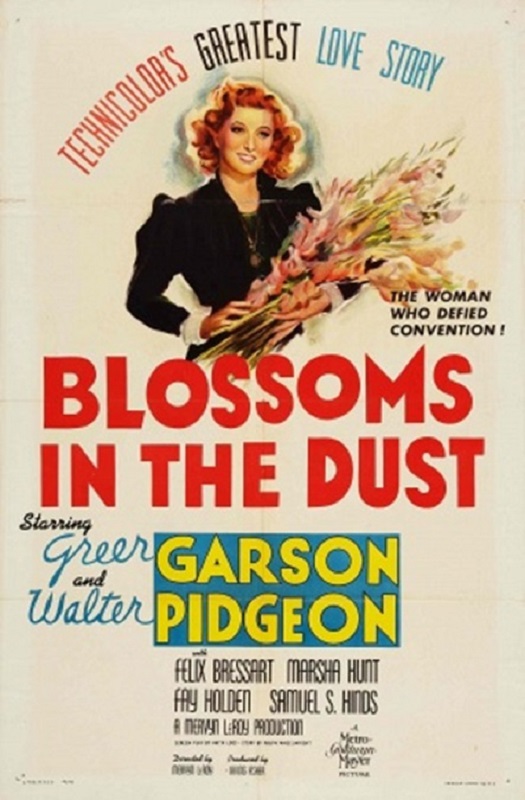

1941 – Greer Garson

Blossoms in the Dust

I liked Greer Garson in this movie, but I didn’t love her. She was good but not great. Yes, some of it had to do with the way the character of Edna Kahly Gladney was written, but at the same time, some of it was the way Garson played her. She was very unrealistic. She was so saintly and good that she almost felt fake. Nobody is that sweet, loving, and unfalteringly perfect. Throughout the film, she displayed near-god-like powers of wholesomeness and sweetness. But darn it if she wasn’t a pleasure to watch.

The character of Edna was based on a real woman who not only cared for orphaned infants and children, but she fought to have the stigma of their illegitimacies be removed from their birth records so they could live their lives without the shadow of shame turning them into social pariahs. Yes, the woman did wonderful things, but even real saints were human and had flaws. But not Garson. She was sheer perfection, and she looked gorgeous doing it.

Garson had an aristocratic air about her. She had poise, and grace, and beauty. She had style and personality. She looked flawless whether she was in love, or had just given birth, whether she was pleading a passionate case in court, or was weeping over her dying husband. But I think her performance, though good and sweet, could have been taken to another level if she had shown us a deeper, care-worn countenance, a sense of exhaustion or worry, or maybe even eyes that were haunted by the death of her only son.

But I don’t want it to sound like I didn’t enjoy watching Garson. I did. But could you imagine how much more impactful Edna’s story could have been if she’d ever shown a moment of deep weakness, or maybe even a short temper. True, there was that one scene when her husband brings home an orphan to replace her son. She shows a little bit of anger and grief, which is undercut in the very next scene, when she accepts the child into her heart. I guess my real problem with her performance was that she played a caricature, not a character. She was an idealized saint, not a real woman. But I enjoyed watching her anyway.