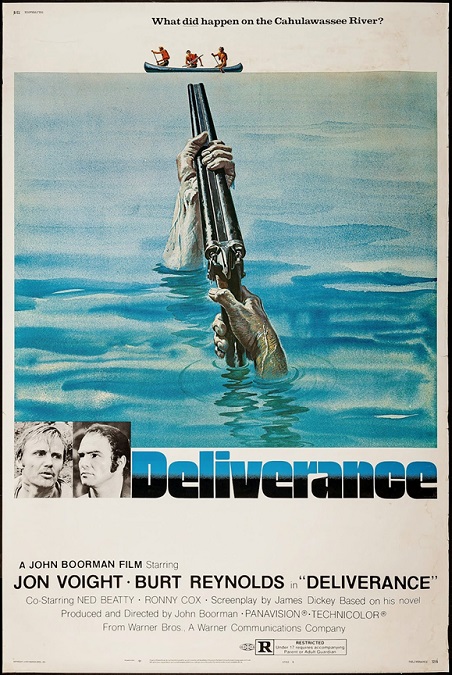

Deliverance – 1972

In the 1970s, movies seem to have taken a turn towards realism, as if audiences were tired of fantasies and were ready for more serious kinds of entertainment. Well, maybe that statement is only half true. They seemed to have wanted films that were dynamic and maybe even shocking. They wanted more in–your-face action and more drama. And while realistic characters, sets, costumes, and props became more common, realistic plots and premises seemed to take a back seat. Still, gone were the happy musicals and screwball comedies of the previous decades. Deliverance was certainly a perfect example.

This movie contained graphic violence, mild nudity, rape, murder, deceit, and mangled bodies. Fortunately, I can’t see where any of it was gratuitous. The problem was that the plot was slightly unrealistic, which was actually ok. I’ll explain. Deliverance was about four friends who were all city boys. Their leader was Lewis Medlock, played by Burt Reynolds, though the main character was really Ed Gentry, played by John Voight. With them are Bobby Trippe and Drew Ballinger, played by Ned Beatty and Ronny Cox.

The film is praised by critics as a man against nature drama, but that was only part of the plot’s conflict. Lewis is a kind of militant tree hugger who is angered by the fact that a river in a remote area of northern Georgia is going to be dammed, destroying the natural environment. So he convinces his three friends to go on a camping and canoe trip down the river. The problem is that Lewis is the only one of them that knows anything about canoeing.

Still, it is all fun and games until they run afoul of two backwater hillbillies who, upon meeting Ed and Bobby, immediately decide they want to rape them. Ok, here is where the premise of the film gets unrealistic for me. True, it made for some intense drama and the graphic nature of the rape scene is appropriately difficult to watch, but in reality, what is the actual likelihood of them running into insane rapists?

But alright. This is not the story of four men who didn’t run into insane rapists. So now, instead of man against nature, the film is about man against man. In a famously violent and graphic scene, Bobby is sodomized by the Mountain Man, played by Bill McKinney as his buddy, the Toothless Man, played by Herbert “Cowboy” Coward watches, his shotgun at the ready. Bobby’s pathetic grunts of pain and humiliation as it is happening really drive the horrible action of the scene home. Plus there is the fact that it doesn’t end quickly. It goes on long enough to make the viewer feel really, really uncomfortable.

Ed, who has been made to witness the whole thing, is forced to his knees as the Toothless Man utters that famous line, “He got a really pretty mouth, ain’t he?” But then there is the awesomely satisfying moment when Ed looks behind the hillbillies and sees Lewis carefully aiming his bow and arrow at their backs. He shoots and kills the rapist while the other man gets away.

Then the focus shifts again, and the film becomes one about man against his own nature. There is an argument about the morality of hiding the body of the dead man and running, which is exactly what they do. But then everything goes wrong. The escaped hillbilly starts to hunt them and kills Drew. The inexperienced canoeists fall over a waterfall, destroying one of the boats and horribly breaking Lewis’s leg. And to make a long story short, Ed hunts the Toothless man and, defying his own nature as a man of peace, kills him.

It was a memorable film, which was well-acted with some intense drama and some exciting action. Sure the premise was just a little far-fetched, but that made it no less enjoyable to watch. Just don’t watch the movie and think that every mountain man in Georgia will rape you at gunpoint. Some citizens of Georgia were actually offended by the movie, saying that it gave them and the state a bad reputation.

And finally, I have to mention the famous and fun Dueling Banjo scene in the beginning of the movie. Lewis, who had brought his guitar, is playing a few chords, when a young boy, apparently a severe idiot savant, starts responding to the music with his banjo. If you’ve never heard the song Dueling Banjos, look it up on YouTube. The creepy, young, inbred boy was played by Billy Redden, an actor who was neither inbred, nor an idiot. But he sure was an amazing banjo player! Just watch his fingers fly over the frets of that banjo!

Anyway, this film also has the virtue of showing just how dangerous and unforgiving nature can be to the unprepared. And camping, like all dangerous things in life, should be actively avoided if at all possible. Now squeal like a pig! Weeee! Weeee!